When Ama, a 43-year-old woman, first noticed a painful rash on her forehead, she didn’t think too much of it. It came and went.

But two months later, she woke up with her left eyelid drooping and her vision blurred. Something wasn’t right.

Ama, who has been living with HIV and managing it with antiretroviral therapy, had developed more than just a lingering issue from an old rash.

She was now facing Orbital Apex Syndrome, a rare and serious complication of Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus (HZO), also known as shingles of the eye.

Herpes zoster, the virus behind chickenpox, never fully leaves the body.

It hides in nerve cells and can reactivate years later, especially in people with weakened immune systems. For most, it causes a painful skin rash. But for a few, like Ama, it strikes deeper.

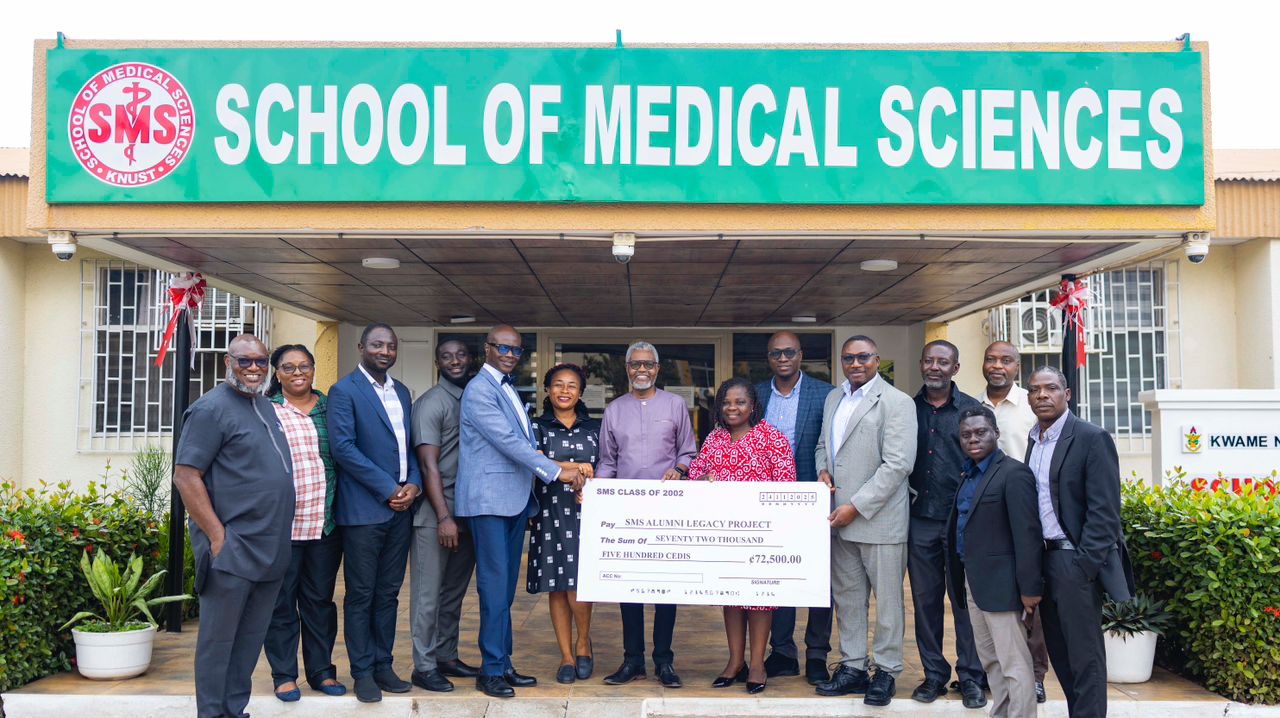

In her case, the clinicians from the School of Medical Sciences found that the virus had reawakened in the nerves of her face, targeting the eye area and leading to damage around the very back of the eye, an area known as the orbital apex.

This is a tightly packed zone where critical nerves and blood vessels pass through. Damage here can cause serious consequences: drooping eyelids, eye movement problems, and even vision loss.

By the time Ama arrived at the eye clinic, she had full drooping of the left upper eyelid, limited eye movement in all directions, and her vision in that eye had deteriorated to 6/36, meaning she could barely see clearly across a room.

An eye examination revealed inflammation, swelling of the cornea, and signs that the optic nerve wasn’t working properly.

Doctors ordered a CT scan to rule out other dangerous causes like tumors or abscesses. Once confirmed, the diagnosis was clear: Orbital Apex Syndrome from HZO.

Ama was placed on a 30-day course of oral acyclovir, a powerful antiviral drug, along with steroids to reduce inflammation. Topical medications were added to soothe and protect her eye.

Over time, her condition improved. The drooping eyelid lifted, her eye movements partially returned, and her vision improved dramatically to 6/12 which was enough to go about her daily life with much more ease.

But her journey took a turn again. Ama stopped coming for checkups and defaulted on follow-up care for 11 months. When she finally returned, doctors found a corneal scar, likely caused by a silent complication known as a neurotrophic ulcer, where the eye loses sensation and becomes vulnerable to injury and infection.

Ama’s case, though rare, holds powerful lessons for patients and healthcare providers alike.

“Orbital Apex Syndrome is not commonly seen, but when it occurs, especially in immunocompromised individuals, the effects can be devastating if left untreated,” says one of the doctors involved in her care.

The good news? Even with a late diagnosis, treatment worked. Ama’s story proves that early detection, prompt treatment, and patient follow-up can turn around even the most serious complications.

It was published in the Ghana Medical Journal in 2021.

Authors

Dr. Esinam Ayisi-Boateng

Eye Clinic, Kumasi South Hospital, Kumasi, Ghana

Dr. Nana K. Ayisi-Boateng

Department of Medicine, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana

Dr. Kwadwo Amoah

Eye Clinic, Kumasi South Hospital, Kumasi, Ghana

Dr. Boateng Wiafe

Operation Eyesight Universal, Accra, Ghana